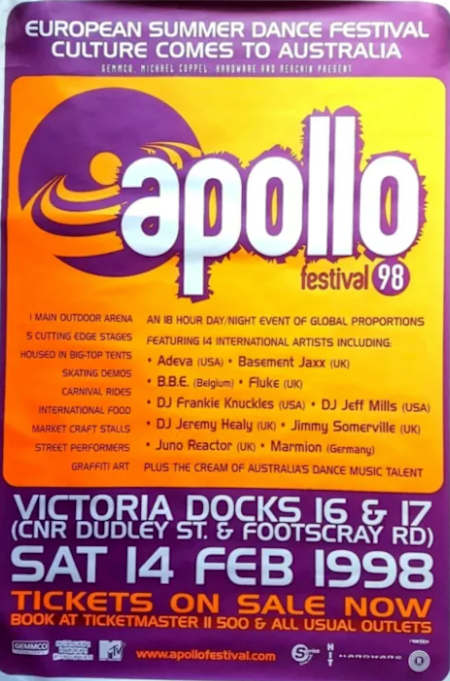

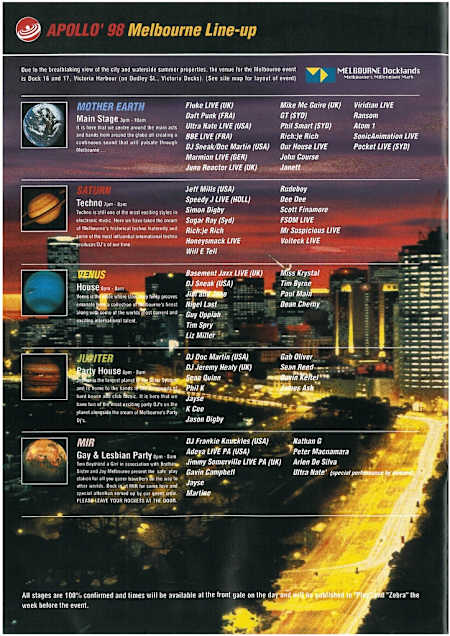

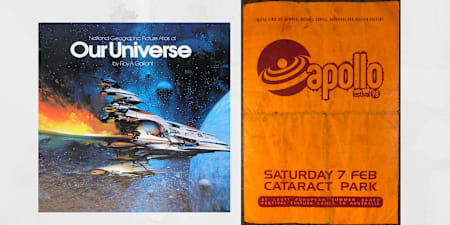

In late 1997, word was out about a new kind of dance music gathering landing in Sydney and Melbourne. ‘European Summer Dance Festival Culture Comes To Australia,’ the poster read. Underneath, in unmissable white font, was the name of this plucky newcomer: the Apollo Festival ‘98.

Apollo promised something different from the standalone outdoor raves like Earthcore and Happy Valley, and bigger than the Hardware techno blowouts at Melbourne’s Shed 14. It was the country’s first dedicated electronic music festival, bringing 14 international artists to Sydney and Melbourne across two weekends.

The dates were set for late summer: Saturday, February 7, 1998 at Cataract Scout Park outside Sydney, and the following Saturday at Melbourne’s Docklands. Gates opened at 3pm, with music until 10am on Sunday. The pre-Christmas ticket price was $65, plus booking fee.

It wasn’t an ideal of European-style raving that made the poster pop from telegraph poles. Apollo was sold on its acts, stretched across an ‘18-hour day/night event of global proportions’.

Those names included Frankie Knuckles, Jeff Mills, Adeva, Ultra Nate, Basement Jaxx and B.B.E. UK big beat group Fluke was top-billed on the main stage. A little further down the list, appendaged with a helpful ‘(FRANCE)’, was an upstart act called Daft Punk.

Apollo ’98 conjured a lineup that, in more ways than one, would be impossible today. The festival perfectly illustrated the zeitgeist moment of a scrappy rave scene going legit. It also secured the Australian debut of a generation-defining dance act.

And yet Apollo was a financial failure, never to return. This is the story of a one-and-done festival well ahead of its time.

Apollo ’98 conjured a lineup that, in more ways than one, would be impossible today

In December 1997, as ravers in Sydney and Melbourne swung by Reachin’ and Gaslight Records for their Apollo tickets, Daft Punk came to the end of a year-long live run.

The Daftendirektour, later immortalised on the Alive 1997 album, covered the UK, Europe and North America from January to December.

Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo were a few years off from the robot helmets, but they still preferred the shadows. The Daftendirektour brought the duo’s studio set-up to the stage, where they worked the drum machines, synths and sequencers to peak exhilaration.

The teenaged producers first emerged on Scottish label Soma Records, which clued in early to their unvarnished genius. The audacity of ‘Da Funk’, Daft Punk’s true breakout on Soma in 1995, is still startling. It precipitated the duo’s jump to Virgin Records, the major label offering the most freedom.

Released in 1997, Daft Punk’s debut album, Homework, morphed into a phenomenon throughout the year. Right at the album’s gleaming centre was hit single ‘Around The World’ -- seven ecstatic minutes of house music going pop.

Apollo got its offer in right before Daft Punk truly blew up. In dance world terms, it’s akin to Big Day Out booking Nirvana for its first-ever festival in 1992.

-----------------

By 1997, Melbourne DJ and promoter Richie McNeill had a proven track record. His Hardware parties with DJs like CJ Bolland and Melbourne’s Will E Tell drew up to 5000 ravers.

But McNeill had bigger aspirations. Still in his 20s, he linked up with Jeremy Jolson and Terry Thompson, who formed a company called Gemmco. Hardware’s speciality was techno, and Gemmco’s house. Thompson, a UK expat, worked with the Cream club brand in Liverpool. The trio shared a vision for an all-electronic festival, but they needed financial backing.

As it happened, Jolson’s parents knew top rock promoter Michael Coppel, who agreed to meet the dance strivers with the big idea. Apollo was on its way.

This oral history of the two weekends in February 1998 is drawn from the people who were there.

For many, the recollections are hazy at best. (“I’m sorry, I have no memory of playing this,” one DJ replied to an interview request.) Others, like McNeill, can talk about Apollo as if it was yesterday.

A lot changes in 22 years. These interviews, conducted via phone and email, were often arranged around new careers and kids’ schedules. Together, the memories make up an overlapping, reverent and sometimes contradictory account of Australian dance music’s coming of age.

Contributors

Richie McNeill: As the founder of Hardware, Richie McNeill has championed techno in Melbourne for 30 years, with recent ventures including PURE and Babylon. McNeill also co-founded the multi-genre Stereosonic and its successor Festival X, which launched in 2019. In 1998, following a stint as Director of Dance at Mushroom Records, McNeill was deep in the world of DJing and throwing Hardware raves.

Phil Smart: A key player in Sydney’s nascent early ‘90s rave scene, Phil Smart is one of Australia’s best DJs. In 1998, Smart ran the anything-goes club night Tweekin every Friday alongside DJs Sugar Ray and Ken Cloud. He and Ray also threw the techno-leaning Sabotage parties. The pair were brought on as ‘local coordinators’ for Apollo in Sydney.

Doc Martin: A longtime champion of underground music in Los Angeles, Doc Martin heads up the Sublevel label and parties. In 1998, Martin was already a repeat visitor to Australia -- even helping to stage an LA offshoot of Sydney’s RAT parties in the early ‘90s. At Apollo, he was booked to DJ solo and close the main stage alongside DJ Sneak.

Jeremy Healy: A former member of short lived ‘80s pop group Haysi Fantayzee, Jeremy Healy co-founded the dance label More Protein with Boy George. The DJ’s Fantazia mix-CDs captured a big room UK sound of the ‘90s. In 1998, Healy released Fantazia: British Anthems, featuring the likes of CeCe Peniston, Jaydee and Fatboy Slim. He played on Apollo’s ‘Party House’ stage.

Tim McGee: A 30-year veteran of the Australian dance music industry, Tim McGee is currently CEO at TMRW Music (formerly Ministry Of Sound Australia). In 1998, McGee was on the Sydney DJ hustle, with recurring slots at Sublime at Pitt Street. In the daylight hours, he honed his house knowledge at Central Station Records.

Simon Digby: A dance music lifer, Simon Digby is Managing Director at Roar Projects, the team behind Melbourne clubs Alumbra and Ms Collins. In 1998, Digby was Hardware’s operations/production manager. A fast and furious techno DJ, he went on to found the label Wet Musik with Will E Tell.

Simon Caldwell: One of Australia’s most respected DJs, Simon Caldwell is a house and techno authority. In 1998, between DJing every weekend, Caldwell started the pioneering party Mad Racket alongside Ken Cloud, Zootie and Jimmi James. (In ‘99, the party moved from Waverley Squash Club to the Marrickville ‘Bowlo’ -- its home for the next two decades.)

Groove Terminator (GT): After creating the albums Road Kill and Electrifyin’ Mojo in the early 2000s, DJ/producer Groove Terminator is now A&R Manager at TMRW/120 Publishing, with recent work including the History Of House shows at Adelaide Fringe. In 1998, the Adelaide native lived and DJed in Sydney. Newly signed to EMI, he released breakout single ‘Losing Ground’ that May.

John Course: Co-founder of Vicious Recordings and a staple of the Onelove brand, John Course remains one of Melbourne’s most in-demand house DJs. In 1998, Vicious Vinyl was already a mainstay, with early releases from Andy Van and Future Entertainment boss Mark James as Eternal.

In The Beginning

Throughout the ‘90s, Big Day Out was Australia’s reigning national festival. (In 1995, the country’s veteran rock promoters, including Michael Coppel, staged a direct effort to squash Big Day Out with Alternative Nation. Their festival was a bust.)

Big Day Out’s dance stage, the Boiler Room, launched in 1994. Its mystique grew with every rock fan who stumbled into an altogether new world.

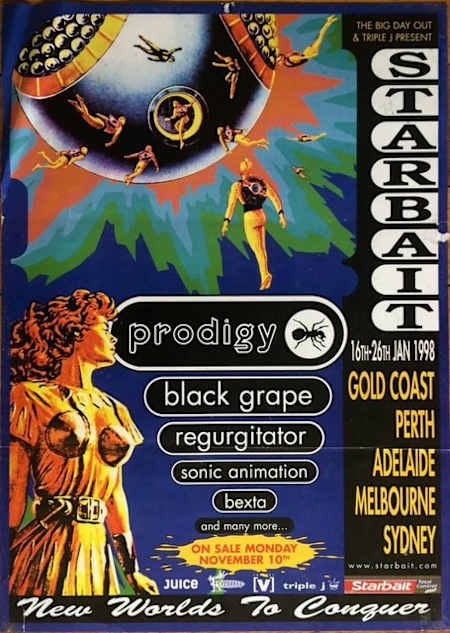

Early on, the Boiler Room showcased locals like Severed Heads, Itch-E and Scratch-E, Groove Terminator and DJ Peewee Ferris. In 1996, The Prodigy closed the room, kick-starting a new era. (They returned the next year as co-headliners with Soundgarden and The Offspring. “It was either play the main stage or not come,” Liam Howlett told Kerrang! at the time.)

With The Prodigy outside in ‘97, Aphex Twin headlined the Boiler Room with teeth-clenching IDM and breakbeats. There was no Big Day Out in 1998, returning the following year with two exemplars of late ‘90s dance culture: Fatboy Slim and Underworld.

The summer of ‘98 seemed wide open for Apollo to make its mark -- if not for Big Day Out planning its own spin-off dance event.

-----------------

Richie McNeill: Before Apollo, when I was at Mushroom, I had a pretty good relationship with [Big Day Out co-founder] Vivian Lees. I was the head of the dance department there for years, so we were constantly throwing acts at Vivian for the Big Day Out. There was always a lot of Mushroom content on the Big Day Out, channelled to Vivian through my boss at MDS, Scott Murphy.

I’d spoken to Vivian for years off-the-record, outside of my Mushroom work, about doing a Lollapalooza-type event [with dance acts]. I was a massive fan of acts like Orbital, the Chemical Brothers and Underworld. After three or four years of talking about it through the ‘90s, it never really happened.

[Lees] basically went and launched a similar kind of concept without me, called Starbait, for January 1998. It was a Boiler Room-type concept with The Prodigy, Regurgitator, Black Grape and Sonic Animation. I thought fuck it, I’ll do Apollo. Starbait got announced, didn’t sell, and was cancelled. It was meant to be three weeks before we did Apollo.

Terry [Thompson] and I had a mutual connection in James Barton, who was at Cream in the UK. I was doing techno stuff, but I appreciated the housey club nights Terry was running. He was good friends with Jeremy Healy too. Terry’s business partner [in Gemmco] was Jeremy Jolson, and Jeremy’s parents were friends with Michael Coppel.

Of all the rock promoters at the time, Michael was the only one who’d try dance stuff. It seemed like a good fit. I joined forces with Gemmco and went to Coppel about doing a festival.

Groove Terminator: Terry Thompson was my agent at the time. He’d been doing these national tours under the Cream brand, which were pretty much the first of their kind. Myself, Sean Quinn and KC Taylor were the Australian residents.

One of the great things about Terry was he really saw the value in building local superstar DJs, which was great for us who wanted to be superstar DJs.

For the life of me, I don't know why the festival wasn’t under the Cream brand. But as far as I understand it, after doing these club tours, Terry saw the potential for a huge, national all-electronic lineup. He went and partnered with Michael Coppel and Richie, who both had the experience and deep pockets to get the festival thing underway.

Simon Digby: I was working alongside Richie from the Hardware camp on the rollout of the concept with Terry and Jeremy. Terry really had his head around the UK club thing. I think what made this event -- and I don’t think there’d been something like it in Melbourne -- was the idea of bringing communities together.

We thought, okay, who’s leading the charge in the gay community? I remember talking to [Melbourne DJs] Gavin Campbell and Arlen Da Silva, who were doing Freakazoid and Savage back then. The concept was quite well received, but people had their questions. Back then, like now, the techno community didn’t want to hang out with the house community, and so on. It was segregated, without being political.

What ended up happening [at Apollo] was probably 20-percent of the crowd went from room to room. And then you had people that were like, ‘This is my room for the whole day.’ But that 20-percent made the festival groundbreaking.

Back then, like now, the techno community didn’t want to hang out with the house community, and so on. It was segregated

Tim McGee: I remember Terry Thompson -- who had befriended a lot of the Sydney scene, myself included -- starting to talk up the plans. It seemed slightly fanciful at the time, as no one had really tried to put all the different scenes together under one banner. His enthusiasm and hyping skills were infectious, though. I was a believer leading up to the show.

Building The Lineup

Daft Punk made Homework in Bangalter’s bedroom, wearing headphones to spare the neighbours. They never got too obsessive. In a 1997 interview with Swedish magazine POP, Bangalter estimated their work-rate at “maybe eight hours a week for five months”.

While both guys kept a low profile, Guy-Man was the especially quiet, contemplative one. The teenage Bangalter, whose father made disco and funk as Daniel Vangarde, had swagger.

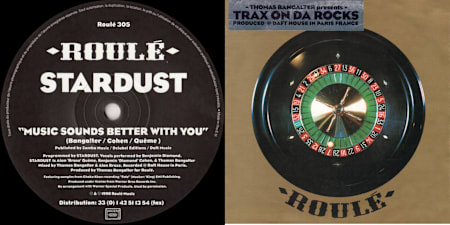

Outside of Daft Punk, Bangalter started the label Roulé in 1995. Initially an outlet for his own Trax On Da Rocks EP, Roulé put the young house head in the orbit of US luminaries Romanthany, Roy Davis Jr. and DJ Sneak. (At stops on Daft Punk’s 1997 live tour, DJ Sneak was the special guest.) If not for Bangalter’s Roulé connections, Daft Punk might’ve skipped Apollo.

Beyond the kids from Paris, Apollo’s lineup is a microcosm of a transformative era. A decade on from acid house soundtracking the UK’s so-called Second Summer Of Love, dance music was between its rave roots and mainstream acceptance.

Apollo had confirmed masters of their genre (Frankie Knuckles, Jeff Mills), the voices of many tingly ‘90s dancefloor moments (Ultra Nate, Adeva), purist DJs with deep crates (DJ Sneak, Doc Martin) and newcomers on the cusp of a breakthrough (Daft Punk, Basement Jaxx). Other bookings -- such as B.B.E., Fluke and Marmion -- exist in a perfect 1998 bubble.

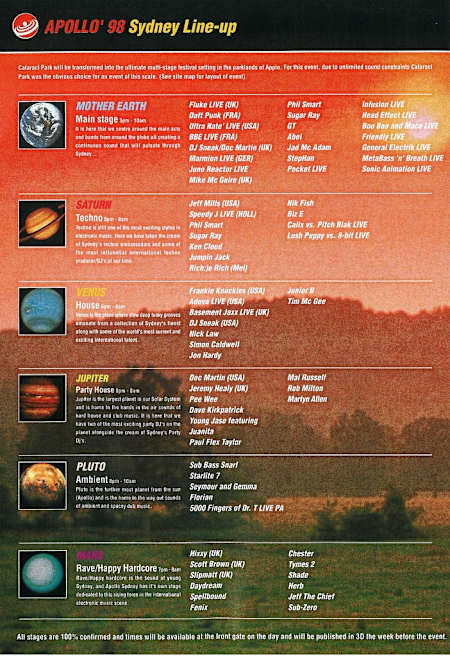

With an 18-hour runtime, Apollo also gave prime slots to local DJs and live acts. While Sonic Animation and Groove Terminator did both cities, Sydney and Melbourne each had its own distinct DJ lineup. (Melbourne authority Janette Pitruzzello, aka DJ JNETT, both DJed and filmed a roaming segment for ABC’s Recovery. “It was my favourite one of my whole two years on the show,” she recalled on email.)

The internationals moved tickets, but the locals grounded Apollo in the energy of a grassroots scene.

-----------------

Richie McNeill: Myself and Terry [Thompson] did most of the bookings. I’d been touring Ian Pooley and Terry had been touring DJ Sneak for years. Sneak and Ian Pooley were in the studio with Daft Punk at the time. I wasn’t getting a response to the Apollo offer and wanted to know what was going on. The agent wasn’t taking it seriously.

We put a lot of pressure on Pooley and Sneak to [tell] Thomas and Guy directly we wanted to get them to Australia. Eventually we ended up booking them. They would’ve been something like 2,000 pounds per show back then.

Doc Martin: At that time I was coming to Australia three times a year. I guess anyone from the US just created curiosity at that time. I wasn’t the typical US DJ, though. I played acid house and breakbeats and things outside the norm. I would do a lot of overdubbing at the time -- mixing on three turntables, so it’s never the same set twice.

At Cream in Liverpool one night, Sneak and I were, how should I say, a little outside our normal realm. Off our heads, basically. We saw four turntables and two mixers and just went for it on four decks together, live. I think Terry [Thompson] suggested me for Apollo because he’d seen me play at Cream. Back then, a lot of tours would go pear-shaped. We were just happy to have a hotel room.

Richie McNeill: A lot of these acts were at early stages of their careers -- none of them were The Prodigy or an outright headliner yet. It wasn’t a super expensive lineup. [Basement Jaxx] were basically just house DJs then. We got them for 3,000 pounds or something. Felix [Buxton] actually still owes me ten bucks for a pack of cigarettes.

Basement Jaxx were basically just house DJs then. We got them for 3,000 pounds or something.

Phil Smart: Richie and [Gemmco] asked us to advise on how to do Sydney. They’d done the local lineup already for Melbourne, and it was very Melbourne-centric.

The local lineup was a very good snapshot of Sydney in those days. Half of the acts would’ve come through Reachin’ [Records]. The main crew would’ve been a no-brainer. That’s what they got us on for -- we knew who to book. We also had an ambient room with Sub Bass Snarl and Seymour & Gemma. I’ve often lamented that we miss ambient rooms at festivals and parties now.

Because we had a good relationship with Richie through our Sabotage parties, we always tried to build that crossover between Melbourne and Sydney. At the end of the day, Sydney’s house and Melbourne’s techno. Sydney is really tied to the gay scene, the Hordern scene, which was way more housey [than Melbourne].

At the end of the day, Sydney’s house and Melbourne’s techno

I think we had Derrick May and Richie Hawtin for the first time in Sydney in the mid-to-late ‘90s, years after they’d come to Melbourne. Neither of those shows were particularly well attended. Richie [McNeill] would’ve got thousands of people in Melbourne and we couldn’t sell out a show with them in Sydney.

Richie McNeill: I had a real passion for space. When I was in Year 12, I applied to the Defence Force Academy to become an Air Force pilot. They only take 80 applicants. I got down to the last 200, but not the last 80. It was fortunate for me; I got into DJing and being a busboy at [Melbourne nightclub] Chasers.

I had a National Geographic book called Our Universe, so we named all the stages after planets: Mother Earth, Saturn, Venus, Jupiter, and so on. I wrote all the program copy too!

Touchdown in Sydney

Apollo’s international acts flew into Sydney Airport in the first week of February 1998.

Sydney’s festival site was 70 kilometres south of the city at Cataract Scout Park in Appin, also home to the Happy Valley raves. Chosen for its “unlimited sound constraints”, the park was set up with carnival rides, a skate ramp and market stalls.

The open-air main stage featured a cast of locals around Daft Punk, Fluke, B.B.E. and Marmion, with DJ Sneak and Doc Martin closing it out until 10am.

Sydney’s set-up also featured a rave/happy hardcore stage with UK DJs Hixxy and Scott Brown. Meanwhile, a DIY crew including Sydney rave mainstay Ming D rolled up to the site with a renegade sound system. The ground was set for a festival quite unlike the Big Day Out.

-----------------

Richie McNeill: Thomas [Bangalter] landed on the Friday in Sydney with his girlfriend. Guy had a flying phobia, and didn’t end up coming. [Daft Punk’s then-manager] Pedro [Winter] didn’t come either.

Thomas was in his early-20s, a small guy with a French accent and a cute girlfriend, just writing these massive records. He was just so happy to be here. To come all the way to Australia, he was kind of blown away. Thomas was still very innocent -- it was all fresh and about making great music. We went to see kangaroos and I took him to eat Chinese in Chinatown.

Thomas was still very innocent -- it was all fresh and about making great music.

Juno Reactor didn’t come. They were booked for a certain show at a certain fee, but they changed to this new show with 15 people, including tribal dancers from South Africa with bongos. They tried at the last minute to make us pay for 15 more flights and accommodation, but it was too much.

Doc Martin: I think we stayed in the business district in Sydney, and I visited the record stores on Oxford Street. We all went to Manly on a boat. Just good vibes, hanging out. Then the festival felt way out in the bush.

Tim McGee: It was a real rollercoaster of an event. I can remember being excited about playing with Jaxx and all the inside chatter about only Thomas Bangalter from Daft Punk turning up to DJ.

There was a feeling of excitement that this was something special and different from all the large-scale raves that had dominated the scene. At the same time, I knew the promoters had taken a bath on the event and some of them took it worse than others, so there was a weird air backstage.

Phil Smart: [Sugar] Ray and I were really busy that night [as ‘local coordinators’], so we didn’t get to enjoy it so much. I DJed and ran around with a radio, looking after people.

Stuart Hitchings (journalist): I do remember Daft Punk playing a great set that was kind of obvious – every tune an anthem, just about – but had that tension-and-release thing down.

Groove Terminator: Standing just behind Thomas [Bangalter] as he played to an OK-sized crowd was shocking to me and Tim McGee, but he didn’t seem to care in that classic zero-fucks Gallic way.

Richie McNeill: There was a point in the Sydney festival where we thought we’d have to close the main stage down. You could see this massive, crazy lightning storm coming up from Wollongong. It went past us, but we got the rain.

Doc Martin: I played first with Jeremy Healy [in the Jupiter tent] - we were friends, but two different styles entirely. Everyone was in our tent because it was pissing down raining.

Simon Caldwell: It rained. It became muddy in some spots. I had a headache. Things got 4am chaotic. I remember going around all the stages and seeing a great variety of vibes. The house stage was packed most of the night -- Basement Jaxx absolutely killed it. The happy hardcore stage was always fascinating to walk past too.

I remember seeing Ken Cloud warming up for Jeff Mills. Super smooth, perfectly mixed deep techno. Then Jeff came on with three turntables. This was around the time I think he was his most brutal, like a machine playing records with a unique energy and precision -- and a ‘stance’ at the decks that lots of people noted. Bent elbows, stiff neck!

Groove Terminator: I played the main stage at like 6am -- at the same bloody time as Jeff Mills, which really pissed me off.

Phil Smart: I remember pulling up backstage at Jeff Mills. That was the first break I’d had all night. The memory’s as vivid as if I was there right now. We were all standing backstage with our jaws dropping.

You could see from behind how he just smashed through the records. He was on three decks, and was ripping records out and just dropping them down in their covers. It was absolutely amazing to watch.

Stuart Hitchings (journalist): I had a tape that I made just wandering between tents, recording bits and shouting the time into the recorder. There are three or four snippets recorded of Jeff Mills in the techno tent over the course of maybe 90 minutes and they all sound exactly the same.

Doc Martin: The rain stopped in the morning, so it was double the joy.

Tim McGee: [I remember] getting mowed over by Sneak and Doc Martin who were running down the natural amphitheatre slope of the main stage to say hi and couldn’t stop, then watching them devour a few BBQ chickens each before DJing. Frankie Knuckles with the sun coming up was super special and a totally different experience to all the club shows I had seen.

Simon Caldwell: I was booked to play the last hour, from 7am, on the house stage after Frankie Knuckles and Adeva. So I had a long wait for my set, and stayed up the whole night trying to check out the festival as much as possible, while also trying to stay sober enough to play. After Frankie Knuckles.

Frankie Knuckles and Adeva were driven to the side of the Big Top before they went on. I remember seeing Adeva trying to dodge the puddles of mud and get to the stage. She did a live PA for about the first hour of Frankie's set, then Frankie just did his thing. Perfect house music with vocals and dubs in equal amounts -- like one long uplifting song in a perfect deep house mode.

Then, as the sun was well and truly up, I had to go up and say, “Hi Frankie, I'm meant to play next, ummm, ahhh...how are you?” Frankie just gave me a big smile and said “Hi!” and made it clear that he was happy to finish and made me welcome. He was so nice and friendly.

I was very nervous at that moment, but managed to play an hour or so of music to finish off the stage. I think it was okay? I couldn't tell you what I played.

Next Stop: Melbourne

Doc Martin: When we got to Melbourne, I remember we were all walking around the city. And the crazy sound in Basement Jaxx’s ‘Red Alert’ comes from the stop lights in Melbourne. You know that little ‘dee-dee-dee-dee-dee’? They recorded it on a little recorder.

Groove Terminator: Sydney and Melbourne couldn’t have been more different. Sydney was at the super out-of-the-way venue and still felt like one of the older style raves. Melbourne being Melbourne, it had the incredible Docklands, with all the tribes getting down.

Simon Digby: This was the first time we used the venue. Our usual venue Shed 14 couldn’t accommodate it, because we needed different areas. We took over the area where Mirvac is now. It’s now high rises, but back then it was an open car park with one shed, where we had the techno room. We put up a circus tent for the house room.

Richie McNeill: It was just awesome having a massive main stage with Daft Punk and Doc Martin and DJ Sneak playing back-to-back. The Boiler Room tent in Melbourne back then was about 5,000 people, so this was a big stage.

Simon Digby: The techno room was a massive square box, and the trouble was there were big openings at either end. It was quite magical playing alongside Jeff Mills. I remember hearing Plastikman’s ‘Spastik’ on that day, which must have been Jeff. And that’s when Speedy J had ‘Pannick’, a really big track.

Normally you’d play parties to 1000, 2000 people who liked techno. But that night I remember seeing the faces of people from other communities who’d normally never come to a techno party. I haven’t really had another experience that crossed over that much.

John Course: I don’t really remember my set. My outstanding memory is of DJ Sneak. I just remember him with a huge, seemingly never-ending joint the whole time in one hand. Mixing perfectly, with vinyl, while said joint remained well lit. He is, and was then, a technical master and that’s my most vibrant memory of the day: Sneak being Sneak.

Doc Martin: I remember Melbourne, because I was carrying vinyl at the time. Sneak and I closed the main stage outdoors. We did four turntables and two mixers at the same time, DJing simultaneously. It felt like 10,000 people out there. The crowd was really into it, the sun was coming out at eight, nine in the morning. Pretty phenomenal to say the least.

"Sneak and I closed the main stage outdoors. The crowd was really into it, the sun coming out at eight, nine in the morning."

Jeremy Healy: One of the Apollo promoters -- who shall remain nameless to spare his blushes -- and I would have a competition to see who could stay up the longest.

When it got to day four, we were sitting in a hotel suite beginning to nod off. He had on a very loud silk shirt and was smoking a fag. He fell asleep, dropped it on the shirt and set it on fire, which woke him up again. I thought that was definitely cheating!

The Afterwards

Soon after his Docklands set, Thomas Bangalter flew back to Paris. Coming off the gruelling live tour of the previous year, the duo spent the rest of 1998 in studio mode.

That New Year’s Eve, Daft Punk broadcast a scorching Hot-Mix on BBC Radio 1, featuring bumping house from the likes of Basement Jaxx and Bangalter’s Stardust project with Alan Braxe. The timing of the mix, as 1998 became ‘99, foreshadowed the next evolution of Daft Punk.

At 9:09am on September, 9, 1999, Daft Punk emerged from a studio “accident” as robots. ‘One More Time’ was a global hit in 2000, followed by the high-gloss pop perfection of Daft Punk’s second album, Discovery.

The duo next visited Australia in 2007 -- just shy of a decade after Apollo. This time, though, Daft Punk rolled with a lot more than a bag of records.

Meanwhile, back in Melbourne, there was no Apollo comeback. Hardware later joined forces with competitor Future Entertainment on Two Tribes, and Australia’s dance festival boom began in earnest.

Michael Coppel took a financial hit in 1998, but he didn’t give up on dance music -- or Richie McNeill. Two decades on from Apollo, Coppel, now under the Live Nation banner, backed the new Festival X from Hardware and its partner Onelove.

-----------------

Richie McNeill: The numbers just weren’t there at Apollo. In Sydney, I think we did like 11 or 12,000 people. In Melbourne, it was nine or 10,000.

Simon Digby: I think the challenge was bringing the communities together. Back then, I used to DJ a lot of the gay-friendly events in Melbourne, and it was a very private community. Parties like Savage were an escape. The [‘Gay & Lesbian Party’ with Frankie Knuckles] at Apollo probably had 800 people in the marquee. If you’d done it as a solo event, you’d probably have had 2000 [people].

Groove Terminator: Looking back, it was right on the cusp of ‘this thing of ours’ going mainstream. You knew this was going to be the way forward for events. Personally, I was super happy to be out of tiny clubs with shitty PAs and playing for large appreciative crowds.

Tim McGee: I think at the time Terry [Thompson] and Jeremy [Jolson] had come into a very tightly controlled Sydney scene with zero fucks whose toes they trod on. Along with the venue choice, they may have been six to 12 months too early with the concept. The line-up always looked amazing in the following years.

John Course: I don’t think, at the time, many people quite understood the revered status Daft Punk would eventually achieve. ‘One More Time’, arguably their biggest crossover track, hadn’t been released yet. I feel like Daft Punk really became bigger after their first two albums and when they slowed down.

Phil Smart: Apollo was pioneering. The rave scene in Sydney started with a few hundred people in Alexandria warehouses and had gone massive. There was a thread of energy.

The opening of Home, a proper superclub in Sydney, was a real shift. A couple of years after Apollo, we’re onto Sydney 2000 and the start of sniffer dogs. The Games changed nightlife in Sydney. One of the big things for us was having Michael Coppel behind an event like Apollo. We saw ourselves as underground and alternative, so for a rock promoter to dip their toe in our world was significant.

Richie McNeill: It lost over a million bucks, which in 1998 is a lot of money. Basically Coppel just wasn’t into [doing it again]. Jeremy and Terry split up Gemmco, and Terry went back to the UK.

After Two Tribes was born, I think to this day Coppel probably kicks himself a little bit for not going around a second time [with Apollo]. We had our fingers on the pulse. It was a diverse, strange, awesome lineup. Just a year too early.

It lost over a million bucks, which in 1998 is a lot of money

Phil Smart: With a looking glass into the future, you would’ve kept building that relationship between the electronic and rock worlds. At the end of the day, everyone knows you lose money on your first festival...

Jack Tregoning is a freelance writer for Billboard, the Recording Academy/GRAMMYs and Red Bull Music. He tweets at @JackTregoning.