Sometime in the early 2000s, Anu Prasad’s daughter went out for a meal with her friends. Prasad’s memory of what her daughter ate is hazy, thanks to the thick fog at the time.

“She might have eaten some raw vegetable, but I suspect it was a burger because it contains lettuce,” she said.

The aftermath, though, is a shadow that that continued to loom large in Prasad’s home in Gurgaon. Soon after the meal, her six-year-old daughter was diagnosed with neurocysticercosis – a disease in which a tapeworm enters the human brain and it develops cysts that lead to epileptic seizures. These insects enter the human body via leafy raw vegetables like cabbage and lettuce that are commonly used in salads, sandwiches and burgers.

That fateful incident resulted in the absence of lettuce from the Prasad house and a cautious approach to eating out for over a decade. That was until 2016 when Prasad, a deputy dean at Ashoka University, dialed Kaustubh Khare a former student of hers, who was enrolled there as a Young India Fellow.

After a two-year stint as an urban designer, Khare teamed up with Saahil Parekh, his batchmate from IIT-Kharagpur to start Khetify — a start-up that installs khets at residences in the Delhi-NCR region. In July that year, Khare and Parekh installed one of their first urban farms in Prasad’s house.

“I was always worried about cleaning up and washing lettuce from the market but this was growing in my own backyard, so to speak,” she said.

Khetify helps people grow their own vegetables by installing urban farms on patios, balconies, terraces, and any other open spaces in their clients’ homes. The aim is to help people grow their own produce that’s pesticide free and of a higher quality than what’s available in the market.

Veggies are planted in a rectangular box made of thermocol or wood that contains a “potting mixture” made of powdered coconut coir, minerals, neem and earthworm composts. Drip irrigation pipes are installed in the boxes to ensure adequate and waste-free water supply.

Khetify also sends a gardener once a month to people’s homes to monitor the growth of the plants. Parekh claims that within the first year, Khetify had signed up 50 clients to grow daily use as well as exotic veggies like fenugreek, brinjal, coriander, bok choy, rocket leaves and thyme in their homes.

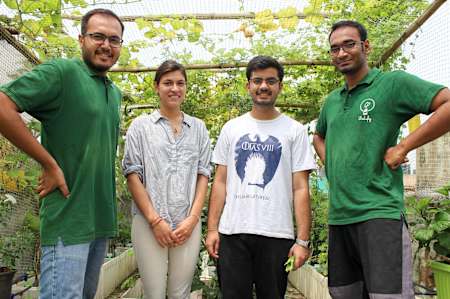

The four-member team, that includes in-house ecologist Shabnam Kapur and gardener Surender Kumar, operates out of a fourth floor apartment in Delhi’s Vasant Kunj neighbourhood. The pad doubles up as home for Parekh and Khare, who’ve converted its 950-square-foot terrace into a mini nursery where they’ve planted 45 vegetables and herbs.

Khetify was incubated in the Aim SmartCity Accelerator Program in February 2016. The initiative helps groom aspiring entrepreneurs and their ventures, by providing financial and legal support, analysing their business plans, connecting them with mentors in the industry, and providing access to government schemes.

After a rigorous pitch session where their business plan was vetted, growth trajectory was analysed and team composition deliberated upon, Khetify was chosen as one of eight startups that would help make cities a better place. But Parekh and Khare discovered that drawing a business plan was perhaps the easiest part of their venture. Its implementation came with a set of exasperating challenges the biggest one being, quite literally, the root of it all.

Parekh and his team borrowed different types of soil from nurseries in New Delhi. They planted spinach seeds in each of the samples to identify which type of soil yields the highest quality, over a couple of weeks. The result left Parekh and Khare holding their heads in despair.

“Everything was absolutely random. Nothing made sense,” Parekh added. “I’m buying this one particular soil from this one nursery. A week later I go to the guy and ask for a soil sample again and there’s a zameen-aasman (earth-to-sky) difference between these two soil samples.

"Imagine, in Gurgaon someone might grow spinach in 45 days but in Delhi it might take 25 days. It just didn’t make sense.”

It was this problem that led to what he calls Khetify’s first “innovation”.

Instead of soil, they decided to create and use a “potting mixture” made of powdered coconut coir, composts of earthworms and neem and such minerals as perlite and vermiculite. This served two functions -– it resulted in a completely organic and, more importantly, a consistent produce that soil can’t guarantee

“Now, my setup can be anywhere and I can guarantee that a plant can grow in a certain number of days. That doesn’t change,” Parekh said.

But relief came with a headache on the side as local residents complained about the activities of these two men, even calling the police on one occasion. To avoid future run-ins, they’ve hired a warehouse in the Kishangarh village nearby, where their mixture is produced.

The idea of Khetify was conceived when Parekh and Khare were working for The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) and the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor Development Corporation Ltd., respectively. Between 2014-16, Parekh traveled all over India to decipher what growth and development mean to those who lived around 35 energy facilities.

“Tomorrow, for example, the government might set up an oil refinery in some rural part of Haryana. Are the opinions of people living there being considered? Even after the refinery is set up, is it engaging with locals, providing employment opportunities?” he explained. In other words, Parekh had to analyse whether the umbrella of growth would be wide enough to include those who were most affected by it.

It was during this time when the idea of local, self-sustainable and decentralised economies started bubbling in Parekh’s mind. If the idea behind promoting solar energy is to create power where it’s consumed the most, he argued, why can’t the same principle be adapted to food?

“When you start thinking of local economies vis-a-vis food, that’s when you realise that urban food systems are totally messed up and you need to flip that around,” he added. Khare, an urban designer, used his experience of working on the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor in 2014-15, to expand the definition of smart cities beyond efficient electricity consumption and public transportation.

“Fuel and energy keep a city running but food is the energy that runs its citizens,” Khare told his boss at the time, in a bid to persuade him to think about including urban farming in the plan. His request was turned down in favour of “bijli, sadak and paani (electricity, road and water) because agriculture is the job of rural India and manufacturing was the job of cities. Don’t try and mix them up,” said his boss.

Once the industrial corridor was designed, Khare quit his job and went to France on a month-long trip to help with the urban design of Cergy-Pontoise, a town north-west of Paris, where he saw communities teaming up to grow their own food. Upon his return to India, he met Parekh, showed him photos of what he saw in France and the both of them grew their own brinjal, coriander, bottle gourd, and mint in boxes of manure “as a hobby”.

During this beta-testing phase, Parekh and Khare met a seed scientist and a farmer who mentored them on best practices such as checking seed quality and the amount of manure required. The result was a harvest of 50 kilos of vegetables on a 15ft x 30ft terrace on a rooftop in New Delhi’s South Extension neighbourhood where the duo lived previously.

Parekh and Khare claim that Khetify's clients are mostly from the Delhi-NCR region, and either hold senior management positions in companies or run businesses. Prima facie, Khetify has tapped into an audience whose economic status affords them the privilege to be able to practice urban farming. But on close analysis, this demographic belongs to an urban milieu that hasn’t seen farm life up close. In other words, while they may want to reap the bounty of farming, they might not always understand the energy and attention it requires.

“The effort a farmer takes… you don’t know until you do the farming," said Aruna Urs, a fellow at the Bengaluru-based Takshashila Institution and a farmer himself. “It is intense, especially the non-profit plants. Our temperature variations during the day are huge and they [plants] are extremely susceptible to heat strokes and pests,” Urs said.

It took him eight crops and four years to fine tune the method of growing tomatoes. “Even if you don’t change the water within the prescribed time, it will catch a disease. So in one way what Khetify is trying to do is indirectly making people understand what a farmer goes through,” he added.

Equally importantly, this class of people are perceived as those who have caused harm to the very environment that, they now realize, could be beneficial for them. Parekh is acutely aware of this and, although he won’t say it in as many words, Khetify is trying to use this to its advantage.

“We targeted the elite households to begin with because it was, sort of, the lowest hanging fruit,” he added. “They would be the most interested and have the kind of spending power to install these kinds of set ups.” Khetify’s choice of clientele is dictated by the fact that the economics of catering to low-income groups, as well as running a for-profit venture, don’t converge. “There’s an irony in that too,” he said.

The next step in Khetify’s journey is to convert unutilized spaces in the city into commercial farms. The owner of such a patch of land — a rooftop, basement or garden, among others –– would be required to make a one-time payment to Khetify, which will set up the farm. Once operational, the startup will then connect this farmer to buyers so that they can sell the produce at the best possible rates.

In the initial phase, these spaces would be operated by Khetify themselves till procedures like greenhouse structures and water supply control are standardised. Afterwards, commercial farms can be operated by owners themselves under a franchisee model that’ll allow them to use the Khetify brand name.

Parekh’s aim is to avoid imports, come up with local solutions and ensure that setting up a farm at this scale doesn’t require too much money. Is Khetify moving towards commercial urban farming because it doesn’t want to be treated like a glorified gardening service? Parekh concedes that some of his clients don’t have the time to devote to urban farming. But he’d much rather focus on those who don’t have access to open rooftop spaces –– even though their communities might have unused patches of land for Khetify to use –– but still want to consume organic produce.

“The model is a little different but the essence still remains the same - to feed as many people as we can to using food that’s grown locally,” he said.