Gaming

On February 13, 2019, Nintendo made a few headline-grabbing announcements at their latest Nintendo Direct conference. Super Mario Maker 2 is coming to the Switch in June. So is a remake of classic Game Boy title The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening.

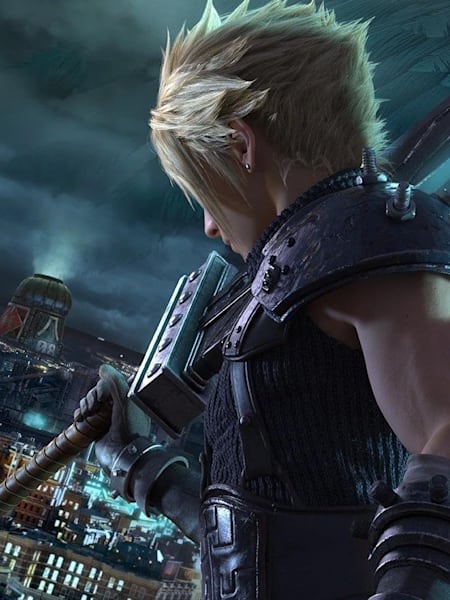

But perhaps most interesting for video-game history enthusiasts are the Switch ports of Sony Playstation's classic Final Fantasy roleplaying titles: Final Fantasy IX, Final Fantasy VII, Final Fantasy X/X-2, and Final Fantasy XII.

The earliest of these games, Final Fantasy VII, which launches on March 26, carries additional, symbolic weight. This game was once set to be a flagship title for the Nintendo 64, but only now, almost a quarter of a century on, will the adventure finally be playable on a Nintendo console.

Final Fantasy, finally

In the world of Final Fantasy VI – the first pseudo-3D game in the series – PTSD-stricken protagonist Cloud is a traumatised young soldier back in the city from the front lines. We never find out much about it, but two continents have been ravaged by war, with the eastern continent ruled by an oligarchy high up in the penthouses of a sprawling, dank megalopolis, Midgar.

We bring this up because there’s an analogy we’re going to attempt to jam in here, like shiny, shiny materia in a weapon slot. You see, Cloud, Sephiroth, Tifa, Barrett et al are indirectly tied to a defining moment in video-game history – when Nintendo walked away from a blockbuster partnership with Sony, and inadvertently gave birth to its strongest competition, starting a war between games creators every bit as bitter.

Nintendo is a company that constantly remakes and reboots itself. Mario, Link and Samus were the faces of Nintendo in the late '80s, and they remain the faces of Nintendo today. This happens via a constant process of rediscovery, by each new generation that finds its personal touchstone within the larger franchise.

Viewed from this perspective, Final Fantasy was, in many ways, the flagship Nintendo franchise that should have been. Developer Square viewed itself as a second party developer for Nintendo, and for many years, Final Fantasy and Nintendo were synonymous.

The original title, released in 1987, launched exclusively for the Famicom/NES home console. It became Square's top seller – the most popular RPG in Japan aside from Dragon Quest by Enix; Square and Enix would later merge and become the Square Enix we know and love today.

Five subsequent Nintendo-exclusive titles followed from there. Two of those titles became global blockbusters outside of Square's native Japan: Final Fantasy IV, which became known outside of Japan as Final Fantasy II; and Final Fantasy VI, which was known to the non-Japanese public as Final Fantasy III (stay with us).

Until this point, every Final Fantasy title was been released exclusively for Nintendo: I-III on the original NES, and IV-VI on the Super Nintendo. But for Final Fantasy VII, Square left Nintendo behind.

Instead of launching on Nintendo's brand-new console, the Nintendo 64, Final Fantasy VII launched on the newly developed Sony Playstation. It almost went the other way; before Square was lured away by the massive storage capacity of the PlayStation’s compact disc format (to store all those beautiful computer-generated movie sequences, which still hold up today), it created a tech demo on a platform that would later become the Nintendo 64, rendering FF6 characters in 3D. Magazines at the time were quick to dub this Final Fantasy 7. It wasn’t, quite, but it could have been had executives at Sony not stabbed Nintendo in the back with a buster sword. If you want to know more about that, check out the video below.

It's been often observed that Nintendo's greatest strength – their stubbornness and willingness to carve their own path – is also their greatest weakness. Sometimes, they make counterintuitive, successful decisions like the Wii, a motion-control home console with far weaker hardware capabilities than its direct competitors.

But as Nintendo US president Reggie Fils-Aime said at E3 2006, “[Gaming] is no longer confined to just the few. It’s about everyone.” The Wii favoured a "what you see is what you get" simplicity, in the the vein of its original NES console, and that it made it accessible to as massive an audience as possible.

But sometimes, Nintendo's stubborn dedication to simplicity stymied the company's progress. And one of the most significant instances of this was their failed partnership with Sony.

In 1988, Sony and Nintendo signed a deal to to develop a joint console, as a follow-up to the original 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System. It would have have merged Sony's CD-ROM technology with what we now know as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

But the deal went south in 1991.

The president of Nintendo at the time, Hiroshi Yamauchi, had ruled over the company since 1949; he shepherded them from their humble beginnings as a playing-card manufacturer to the hardware and software behemoth they became. He was infamously stubborn and a hardline bargainer; unbeknownst to Sony, Yamauchi sent Nintendo representatives to Phillips to negotiate better terms on software licencing. And at the 1991 Consumer Electronics show, Nintendo announced their new partnership, catching Sony completely unaware and embarrassed.

The Philips deal would also eventually fail; the Super Nintendo, or Super Famicom as it was known in Japan, moved forward with a cartridge-only format. But fast-forward four years, and Sony launched their own hardware, the original Sony Playstation, in December 1994. The former collaborator had become Nintendo's direct competitor, as evidenced by the commercial below:

The Sony Playstation featured games stored on CD discs rather than cartridges. And although disc would eventually become the predominant medium for games, Yamauchi's stubbornness reared its head again; the company would keep cartridges for the Nintendo 64, rather than embrace the future.

Everyone, including the brass at Nintendo, knew that CD technology would be king. But for Yamauchi, the technology had not progressed to the point that they could stand behind it. It was an issue of load times and security flaws; the CD-ROM format lent itself to rampant pirating, and Nintendo were (and still are) fiercely protective of their intellectual properties.

Even in its infant state, the CD format provided enough storage for voice acting and movie clips. The associated hardware allowed for a better framerate per polygon than cartridges. Nintendo's hardware was simply not capable of replicating Square's vision, and this was despite Square's repeated, ignored advice: that Nintendo needed more powerful hardware and a CD-ROM drive to stay competitive and attractive to third-party developers.

Nintendo had unshakeable confidence in their first-party brands. The hardware was good enough to serve their own software needs, and thus, everyone else would need to adjust: take it or leave it. And after several failed tech demos, which convinced Square that the Nintendo 64's hardware was irreconcilable, they decided to leave it.

Once Square made this final decision, they and Nintendo were not on speaking terms for five to 10 years, depending on who you ask. On the surface, things seemed fine – Nintendo publicly wished their former partners well on their future endeavours – but the general belief among Square employees was that once they left Nintendo's partnership, they were never coming back.

The aftermath is established history. The Sony Playstation went on to outpace and outsell the Nintendo 64. It was also during this time that Sony created strong partnerships with multiple third-party developers; it was more expensive for these companies to develop for a cartridge-based system than for a CD format. Nintendo, meanwhile, turned further inward and first-party focused; the company has never recovered its third-party support since those early days.

Final Fantasy VII, the point of contention and the first 3D game in its franchise, became a critical, commercial success. Set in a post-industrial world, the main protagonist is mercenary Cloud Strife, who fights for good against the Shinra Electric Power Company, a greedy corporation bent on harvesting and draining the planet's Lifestream for energy. Along the way, Cloud meets likeminded characters such as mage and love interest Aeris Gainsborough. He also learns about his dark past and the unreliability of his memories, which he discovers might be false.

The game's fantasy-meets-sci-fi vibe has since become ubiquitous in the RPG genre. Its animated cutscenes – one of the main reasons why Square left Nintendo to begin with – were well-shot and emotionally rendered, and they showcased the early, cinematic capability of video games to tell stories. And fittingly, none of the games in the core Final Fantasy series have launched on a Nintendo console ever since.

The game’s return now is all the more surprising given that Final Fantasy VII has been ported to almost every conceivable console besides Nintendo. A PC port in 1998 exceeded sales expectations. It was released as a PSOne Classic title on the Playstation Network in 2009. It was re-released, with additional features like cloud saving and character booster (to decrease grinding and difficulty) for PC and Steam in 2012 and 2013, respectively. There was an iOS release in 2015, followed by an Android release in 2016. It was released on the mini-console Playstation Classic in December 2018. There’s even a Final Fantasy VII Remake on the way from Square Enix, although its unknown release date appears as far off as ever. For now, just enjoy the trailer:

But now, over two decades since the original rift, Nintendo players will finally be able play those lost Final Fantasy games on a Nintendo console, all in the space of a year. For younger gamers, these will be brand-new experiences – a chance to rediscover and experience classic games in a new format. Those who've never understood why Final Fantasy VII has been held in such reverence (it’s the music, it’s the story, it’s that twist, it’s everything) in particular can now finally find out for themselves – and on the go.

Without spoiling things too much, a scene late on in Final Fantasy VII jumps forward 500 years, with surprising emotional impact. It’s not been quite that long, but it sometimes feels like it. For those of us with long memories, Final Fantasy VII’s arrival on Nintendo Switch will be a 'welcome home,' long overdue after literal decades of awkward estrangement.