When hip-hop culture burst into the mainstream consciousness in the States, it was a culture almost fully-formed.

Four different disciplines came together to create a movement that spanned to globe and changed it for good: graffiti broke out onto New York City’s walls and train cars, proclaiming the territorial dominance of one mysterious name: TAKI 183; a young man who would be known as DJ Kool Herc put two turntables together and mixed funk and soul breaks into uninterrupted rhythm; The Furious Five emcees, led by their own DJ, Grandmaster Flash, showed the urban audiences of mid-70s NYC what it was like to be a master of ceremonies; and an acrobatic youth nicknamed Crazy Legs jumpstarted a movement to spread the gospel of breakdancing around the world, helping to form the Rock Steady Crew, one of hip-hop’s first organised collectives.

Of course, nothing really happens overnight. It took four years between DJ Kool Herc’s first block party on Sedgwick & Cedar in South Bronx to Rock Steady’s formation in 1977, and another six years before the Rock Steady Crew made their historic tour of Japan in 1983, permanently leaving a mark on Asian urban culture. It took unquenchable passion, a lot of hard work, and just a bit of luck (not to mention the ridiculous mainstream success of Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979).

And how long did it take for hip-hop culture to reach Malaysian shores?

The Malaysian chapter of hip-hop’s spread did not occur the same way it did in the States. There were no innovative block parties that jumpstarted a movement, no silver-tongued Mic Controllers moving the crowd with witty rhymes. Graffiti on walls in inner-city KL were crude and basic at best, not the work of aerosol artisans.

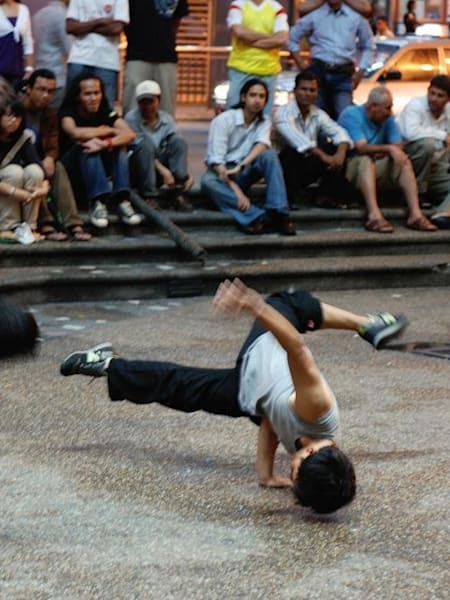

Hip-hop culture in Malaysia began with the b-boy.

There was no overwhelming tsunami of hip-hop subculture adoption in KL, or any other part of Malaysia. The streets were not suddenly awash with posses of hip-hop heads, hijacking lamp posts to power up their soundsystems. KTM trains were not inundated with “bombs” and “burners”, slang for carriage-long murals.

For Malaysia, hip-hop began with the most accessible part of its culture, adopted by the largest demographic it could possibly appeal to: disenfranchised urban youth, hungry for a new avenue of creative expression.

Although passionately inspired by landmark tracks like “Rapper’s Delight”, and subsequently Blondie’s “Rapture" in 1980 and Herbie Hancock’s 1983 hit “Rockit” – and all the vivid imagery that fresh new music brought with it - Malaysia’s first hip-hop fans found it difficult at first to emulate and adopt the new counterculture emerging from the street corners of South Bronx.

"Rapture" by Blondie (1980)

“Rockit" by Herbie Hancock (1983)

Aspiring DJs had an almost insurmountable obstacle: turntables and sound systems were prohibitively expensive, and vinyl records were still in limited supply. Sure, you could buy a Sharifah Aini LP from the music store (which were still a thing, back in the 80s) and try to scratch it on your father’s old Pioneer tabletop, but it wouldn’t have been the same. (And your father would have killed you.)

Going from a post-colonial English speaker to a modern Shakespeare with a solid stage presence (and a commanding voice) was a challenge that would take years to overcome.

Likewise, Malaysian youths who dreamt of becoming rappers delighting crowds with mic skills also found realising that dream a little difficult: prior to innovations in the craft by early local 90s acts like Nico and Nana Nurgaya, hip-hop rhymes were invariably in English, a second language to most Malaysians, to be sure, but still a foreign tongue to most. It’s one thing to be able to write and converse in English, but the sheer intimidation behind penning a 16-bar verse in English – heavily-slang dependent Ebonics, no less – weighed heavy on Malaysian rap fans who wished to become emcees. Going from a post-colonial English speaker to a modern Shakespeare with a solid stage presence (and a commanding voice) was a challenge that would take years to overcome.

But graffiti was easy, right? No, it wasn’t. As is still being demonstrated by amateurs in the local scene today, one does not simply pick up any old spray can and scribble “[INSERT COOL ALIAS] Wuz Ere” to ascend to the status of street king. Local kids would still have to learn to fully appreciate the value of (and procure!) specialised equipment. Spraycaps, specialised Krylons, and protective face masks were still a pipe dream to many Malaysian hip-hop fans in the early 80s.

It was the b-boys who had to pick up the gauntlet for Malaysian hip-hop.

WordsManifest is a founding member of The Rebel Scum and the Rogue Squadron hip-hop collective. He was the co-editor of DJ Fuzz’s book The Way of the DJ. Words is also a photojournalist and the Editor of hyperlocal newsportal CoconutsKL.