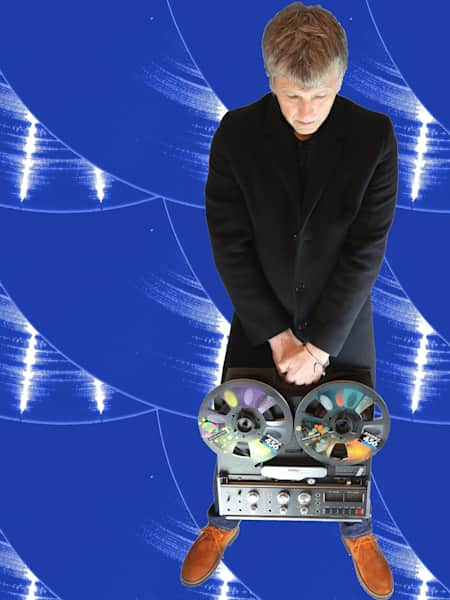

"I just got into this idea of cutting tape up, I loved it." Cradling the phone in his Merseyside home, Greg Wilson is reminiscing about his groundbreaking experiments with 're-edits', the practice of using reel-to-reel tape to cut and paste parts of existing songs to form new ones. "It was a great hybrid time of experimentation," he continues, his voice betraying an obvious fondness for the late-'70s and early-'80s period he's referencing. "There was so much creativity. Editing became second nature for many years, I just cut tape up!"

He laughs as he finishes the sentence, aware of the understatement. Greg Wilson didn't just cut tape up. Born in 1960, he started DJing at 15 and, less than a decade later, was appearing on Channel 4's legendary pop culture show The Tube demonstrating how to mix two records in front of an excitable Jools Holland. As well as mixing, Wilson – an electro-obsessed resident at Legend and later The Haçienda – also pioneered the re-editing movement. Both processes would revolutionise DJ culture.

Watch Greg Wilson on The Tube below.

Shortly after that TV appearance, the then 23-year-old gave up DJing to focus on production. But in 2003, he "stopped being a luddite and got on the internet," coming out of retirement eager to document the black music, dancing and rebel culture that first drew him to Legend. Once again a fixture in the clubs, Wilson is part of this year's Red Bull Music Academy UK tour and plays a hometown show at Liverpool's Buyers Club on Thursday October 8 ( buy tickets). Ahead of the performance, he unspools his story.

It started with an edit

"I started doing radio mixes for Piccadilly Radio Manchester in 1982. We'd go into Legend when it was empty and they'd rig up a reel-to-reel and record me mixing live. If there was a hiccup we'd edit it later at the studio so it was broadcast-ready."

There was no term 're-edit', I called them turntable edits

"One day there was no one there to do it so I went into the booth and before I knew it I was really getting into it, reversing bits of tape and being experimental and playful. I ended up buying my own machine and then the mixes had loads of edits, backwards bits or extended bits. I started to edit individual tracks, they were the first examples of re-edits in this country. There was no term 're-edit'. I called them turntable edits. I sometimes used two copies of the same track and played one behind the other. It was making a new version out of the existing records by cutting them up."

Understand the process

"You're recording a track onto tape and you might want to use more at the beginning and end than the middle. It's as basic as cutting out a section, but you've got to make it seamless, so there's not a big gaping hole for the listener. It's the naturalness of the edit, making it sound like it should be that way."

The greatest ever individual edit is The Beatles' Strawberry Fields

"A really good example was my essential mix for BBC Radio 1, each of those tracks, I had to take them down to a coherent two-and-a-half or three minutes. It had to make sense and get the meat of the track in. Editing can be used to shorten something or to extend something. The greatest ever individual edit is The Beatles' Strawberry Fields. John Lennon had two recordings, one acoustic and chilled, one psychedelic. He liked the start of one and the end of the other. He asked George Martin to fix it and he did. One of the most famous ‘60s records is in fact two recordings. The edit brought them together and made two things which shouldn't have worked, work."

It's all natural

"I found it very meditative. I've had sessions where I've been over the tape machine for well over 24 hours. I could lose myself. For some reason it suited me, I'm not sure why. Even though I wasn't a maths or science person at school, it made sense. I understood that later working in studios talking about specific beats and bars. I was so locked into that idea of beats. My family owned a pub and there were parties and mobile discos coming in an out and when I was a kid I could hear the thud of the beats at night. That instilled a sense of rhythm in me."

A moment of magic

"It's a little bit of magic, two moments made into one continuous moment. I did the first re-edit that was released, a promo-only track by Paul Hague. I just did that by stream of consciousness, when I look back it's just mad. There's no reason to it, it's not done even with a dancefloor in mind, just playing around with tape."

I was using samples of radio stations around the world, spoken word bits, cutting bits up

"An early edit of mine that really made a splash was Frankie Goes To Hollywood's Two Tribes. I thought I'd done something really interesting. It was before Paul Hardcastle got to number one with 19. I was using samples of radio stations around the world, spoken word bits, cutting bits up. I was influenced by an album called Kiss FM Mastermixes – released on Prelude in 1982 – and bootleg 12-inches with tracks cut up into short mixes. Big Apple and Beats and Pieces did them. I started to understand how they'd done it. That Frankie mix was intricate for its time, leftfield and a little bit abstract, which I liked."

Less is more

One of the big editing mistakes is adding unnecessary stuff. That's the person thinking 'have I done enough to this?'. It's a less is more situation. You do as much as you have to, add things in a way that's respectful to the original. If I'm making an edit I'm not thinking of other DJs, I'm thinking about the people who are gonna dance to it."

If you show off, people just won't dance, it won't sound right

"When I did Getting Away With It by Electronic, it's big epic track that ends with a great strings thing, but I liked the idea of having the finish and then it come back again. It's an end of the night tune. I'm thinking about people and how it's gonna impact in that moment. If you show off, people just won't dance, it won't sound right. You're working on a tried and tested track, something that knows the dancefloor more than you know the dancefloor. Some people think they are the edit, but the track is the genius and the editor is the facilitator. Don't forget that these are great records made by great musicians."

Greg Wilson is on Facebook

Check out more great premieres, stories and videos at RedBull.com/Music

Like Red Bull Music on Facebook and follow us on Twitter at @RedBull_Music