The former professional rider’s epic struggle to reclaim his function and identity has yielded inspiring progress that no one could have imagined.

Paul Basagoitia is riding his mountain bike up a dusty track in the Mount Rose Wilderness, halfway between Lake Tahoe and his home in Reno, Nevada. The incline on the Upper Thomas Creek Trail is steady but never steep, and he’s traveling at a solid clip. On a hot June day, it’s a relief to weave through shaded forest.

A casual cyclist might notice that he’s pedaling an electric mountain bike. An attentive observer might notice that he’s wearing a custom brace on his right ankle. Virtually no one would guess how he’ll struggle to walk unassisted when he dismounts his bike.

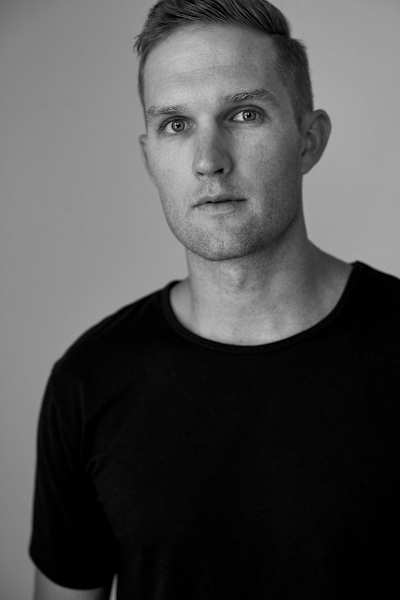

Basagoitia, 33, assumes the role of trail guide, steering through switchbacks, pointing out obstacles, informing his guest of what comes next. From the outside he appears to be at home, but navigating through the trees wasn’t his jam during an 11-year career as a professional mountain bike rider. Instead, Basagoitia’s riding life was spent on the razor’s edge. When he wasn’t competing, he was out finding the steepest, gnarliest terrain imaginable — then blasting downhill and into the air.

It was that type of riding — first slopestyle, on man-made jumps, and later at big-mountain events — that brought Basagoitia a degree of fame and fortune. He was an acrobat on a bicycle, earning a paycheck for pushing boundaries. And it was that type of riding that left him with a life-altering injury to his spinal cord at the Red Bull Rampage in October 2015.

Now, four years later, a documentary about his ongoing rehabilitation is poised to bring him a new degree of fame. "Any One of Us" will break hearts and inspire courage in equal measure. More than anything, the film presents a stark, honest depiction of what it’s like to live with a spinal cord injury (SCI).

After a spring and summer making the rounds on the film festival circuit, the Red Bull Media House–produced documentary was picked up by HBO and is set to premiere on Oct. 29, almost exactly four years after his accident. Back on the bike now and surpassing his doctors’ expectations, Basagoitia has become an inspirational figure for the SCI community.

It’s a bittersweet development for a relatively private man who never sought fame but rather found solace from a turbulent childhood on the bike. Basagoitia wanted to be known for progressing the sport, and he’s understandably agitated by the thought of being remembered for one small but consequential mistake.

“I’m a little overwhelmed thinking about the HBO release,” Basagoitia says in August. “I still have a lot of friends and family members who haven’t seen the film. I didn’t hold anything back, and I went through some things that these people don’t know anything about. So I guess I’m both excited and nervous.”

Yet the injury is not the endpoint of his story. Pedaling on that dusty trail in the Mount Rose Wilderness, Basagoitia is just another bike rider, flowing through the trees. And for that, he is eternally grateful.

THE CRASH

The Red Bull Rampage is a competition like nothing else in cycling. Pro surfing has its big-wave contest at Mavericks. Rock climbing has the solo ascent of El Capitan. Big-mountain riding has Rampage, among the desert cliffs near Virgin, Utah, an event that draws slopestyle riders, downhill racers and natural-terrain freeriders. It’s held in a rugged and exposed natural amphitheater where 60-foot canyon jumps must be landed within inches of perfection and a light wind can turn glory into anguish.

For Basagoitia, Rampage presented a particular challenge. He’d come from a BMX background and made his name performing BMX-style tricks on a mountain bike. He first competed at Rampage in 2008, finishing 12th. As the sport progressed, he tried to evolve with it. When a new generation of riders began outperforming him, he became the first rider to do a double backflip on natural terrain. But he also grew tired — of the injuries, the pressure and the never-ending hustle for sponsorship.

By putting together a unique run at the edge of the venue, Basagoitia finished a career-best ninth at Rampage in 2014. He felt he could’ve done better, though, perhaps finished in the top three. So that became a final career goal — stand on the box, use the prize money to buy an engagement ring for his longtime girlfriend, Nichole, and retire.

That was the plan heading into the 2015 edition. And even though all competitors had been forced to accelerate their preparation due to an impending storm, for the first half of his run, everything was on track. He’d nailed a backflip over a canyon at the top, the toughest part, followed up with a 270 for flair, then landed a massive step-down.

But he overshot his landing. Not by much, but enough to change his life. While trying to correct, his right pedal hooked a branch of trailside sagebrush. That launched him over an eight-foot ledge, onto his back. Though it was a heavy crash, it didn’t look out of the ordinary by Rampage standards.

Lying on the ground, his first emotion was anger; he’d thought he was on a winning run and had finally put it all together. He’d have a second run — one more chance to win Rampage and retire.

“I’ve taken many harder slams in my career and walked away,” Basagoitia says. “But for some reason I landed exactly on the 12th vertebra, enough impact to shatter it into my spinal cord. I couldn’t move my feet or my legs, and that’s when I knew I was in big trouble.”

Next came a tearful, seemingly endless helicopter flight to the hospital. After CT scans, he was told he would require surgery. That procedure, to remove bone fragments from his spinal cord, lasted more than 10 hours.

He awoke living in what he calls his “new body.” He was classified as a T12 paraplegic. His spinal cord had not been completely severed; he was “incomplete,” meaning there were nerve signals below the injury. Still, doctors told him he might spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

The mountain bike community was in shock. There had been bad crashes at Rampage before, but no one had ever suffered a life-changing injury.

And now Basagoitia was paralyzed.

THE BACKSTORY

Basagoitia pedaled a bike without training wheels when he was 2. He started competing in BMX races at 6. By 10 he was ranked among the top BMX riders in the world. His childhood was spent on the bike. This formative experience laid the foundation for his adult life, but it wasn’t always joyful.

His mother, Jackie, drove him to races and paid his entry fees. But she also pushed him, haranguing him when he didn’t win. “The days I wasn’t doing so well she would scream at me,” Basagoitia says. “As a child, you don’t want to hear that from your mother.” Later in life, he’d be estranged from her for years.

The pressure was intense. Everything at home was intense, including his parents’ fighting. Home was a “beat-up motel with the roof falling off ” that his parents bought when Paul was 9. When he was in the eighth grade they divorced, and his mother stopped taking him to races. His father, Gabriel, moved into a separate room in the motel, where Paul also lived for several years.

His BMX racing days ended at age 14, but his mountain bike career was about to take off. At a skatepark in Minden, Nevada, Basagoitia met a kid from Reno named Cameron Zink, who was doing BMX-style tricks on a 26-inch-wheeled mountain bike. They became fast friends.

Basagoitia’s come-from-nowhere victory at the inaugural Crankworx slopestyle event in 2004 is the stuff of legend. He’d saved money earned all summer working as a plumber to make the trip to Whistler, British Columbia. He borrowed Zink’s bike and won with a backflip onto the final obstacle and a tailwhip off at the biggest slopestyle competition in North America, beating freeride legends like Cedric Gracia, Wade Simmons, Darren Berrecloth and Richie Schley. Finishing third that year was Kyle Strait, who, like Zink, would go on to become a star of the sport and one of Basagoitia’s closest friends.

“I really don’t know any of the riders,” Basagoitia said in an interview after that victory. “I guess I beat a lot of big names. I would like to thank my sponsors, but I don’t have any sponsors, really.”

The following year he returned to Crankworx and defended his title, this time fully sponsored by Kona Bikes. His life would never be the same.

From 2005 through 2009, Basagoitia was among the biggest names in extreme mountain biking. He became the first person to land a 720 on a mountain bike. He performed tricks for baseball fans while aboard a barge floating on San Francisco Bay outside AT&T Park. He bought a property outside of Minden, where he built a slopestyle course and installed a foam pit. He recognized the future of freestyle mountain biking and began converting his slopestyle tricks to big-mountain terrain.

In 2010 he reconnected with Nichole Munk, a blonde cheerleader from his high school days. She attended a party at his house, a private slopestyle contest of sorts. They’d gone to school together but ran in different circles. She was outgoing with an easy smile, the daughter of a police officer and close with her parents; he was a reserved bike park kid from a broken home. He’d had a crush on her back then, but she hung out with football and basketball players. At his house, though, surrounded by friends, Basagoitia was in his element, a well-paid professional athlete living every kid’s dream. They’ve been together ever since.

As Basagoitia found stability in his personal life, he faced professional instability. The sport that had paid for his home and made him a household name within his community was evolving. Production films made way for web edits. A new crop of riders was developing new tricks. He was no longer winning events; he wasn’t even finishing in the top 10.

In an effort to keep up, he was getting injured “left and right.” Though cognizant of BMX rider Stephen Murray’s fall while attempting a double backflip in 2007 that left him paralyzed, Basagoitia decided to attempt it on 26-inch wheels. In 2012, while sponsored by Teva and Kona, he pulled off the first double backflip in natural terrain on a mountain bike. He’d made history, and suffered a concussion, but it wasn’t enough to keep his sponsors.

By 2013, Basagoitia was more or less unemployed. He signed a deal with Scott Bikes, bought some camera equipment and began producing his own web edits. In 2014, he made the finals at Rampage.

THE INJURY

Friday, Oct. 16, 2015, was finals day at Rampage. Organizers made the call to move the finals up one day due to thunderstorms in the forecast. Basagoitia woke up that morning confident but also stressed. He hadn’t yet ridden his entire line, but it was his fifth Rampage, and every rider was in the same situation.

“There was weather coming in,” Basagoitia says. “Instead of waiting it out, they pushed it up the day before and nobody had their lines done. The night before the finals, jumps were not even halfway finished and people were still trying to guinea-pig their lines and falling left and right.”

Basagoitia was among many who crashed that day. Helmet-cam footage, shown in "Any One of Us," captured the moment when Nichole reached him on the ground — the moment their lives changed forever. “I can’t move my feet,” he said, a panic rising in his voice.

He was flown to the hospital in St. George and given a grim diagnosis: He might never walk again. He would have problems with bowel and bladder function, as well as sexual function, possibly forever. In addition to the emotional and physical stress of the injury, he was in a constant state of sleep deprivation; he was woken up every three hours for catheterization and was given blood-thinner shots every eight hours to avoid clotting. In a daze, his mind shifted from thinking about winning Rampage to wondering if he’d ever ride again.

THE DOCUMENTARY

Lying in his hospital bed, Basagoitia had time on his hands — as well as a new DSLR video camera, a GoPro camera and many unanswered questions about his injury. He felt lost and thought he might be able to produce something that would be helpful to others with an SCI. He also hoped he would be able to document his progression. The notion of Red Bull Media House being involved didn’t come up until nearly a year later.

“Here I am in the hospital bed, thinking about how I am going to pay for these bills,” Basagoitia says. “I started shooting my progress and I figured I’d just make a little video, sell it on iTunes or something, and whatever I raised would go straight toward medical bills. I would document everything. I wanted to see my improvements over time. Living in it, you don’t see it. You have to visualize it; you have to see it to have the encouragement to keep going.”

There’s a scene early on in "Any One of Us" that leaves a mark. Alone and naked in a bathroom just weeks after his injury, Basagoitia inserts a 14-inch catheter into his penis in order to empty his bladder. It’s raw — and all the more remarkable considering he shot the scene on his own. “That whole catheter scene, people tell me that is the heaviest part of any documentary they’ve ever seen,” he says.

Prior to that point in his recovery, Basagoitia had a catheter that remained inserted at all times and was emptied by nurses. When they removed it, he was under the false impression that he’d be able to urinate on his own.

When handed the catheter stick, his reaction was understandable: That thing’s not going up me, no fucking way.

“I remember doing it the first time and I just fucking cried. Two weeks earlier I was competing at the highest level in Rampage on national TV — a celebrity, whatever you want to call it — and I went from that to learning how to insert a 14-inch catheter. It caught me off guard, heavily.”

Before Red Bull Media House got involved in the documentary, Red Bull was involved in Basagoitia’s recovery. He’d been a sponsored athlete for years and forged a friendship with athlete manager Aaron Lutze. Lutze was there in St. George when Basagoitia came out of surgery, and he helped arrange for Basagoitia to spend 12 weeks at Craig Hospital near Denver, a top facility for treating spinal injuries. Months later, Lutze visited Basagoitia at home in Reno. On his couch they watched the 2013 HBO documentary "Crash Reel," about pro snowboarder Kevin Pearce and his recovery from a traumatic brain injury. “I knew Paul was filming his recovery, but he didn’t know what he was going to do with it; it was not obvious it was a movie,” Lutze recalls. “When 'Crash Reel' ended, Paul said, ‘I want to make something like this but for spinal cord injuries.’”

After a few phone calls, it was approved. Early on it was understood that all proceeds from the film would go to Wings for Life, the nonprofit foundation started by Red Bull founder Dietrich Mateschitz focused on finding a cure for paralysis.

Basagoitia flew to Los Angeles and met with Fernando Villena, a feature-film and documentary editor who had been tapped to make his directorial debut. From there, Basagoitia began juggling two life-altering realities — living with his injury while living with a film crew.

Asked about bringing a film crew into a home environment rebounding from a catastrophe, Munk admits it was hard. “I wasn’t seeing this as an opportunity for a movie,” she says. “But Paul had an idea from the very beginning — he wanted to make a difference and turn his camera on. He wanted to start filming his recovery, and his journey. I remember hearing ‘We might make a movie out of this,’ and I was thinking, ‘What are you talking about? This is insane.’”

The documentary focuses on Basagoitia but also highlights the range of accidents and experiences that define living with an SCI. Through intermittent vignettes, 17 individuals with SCIs share their stories. Internally, the production team calls them the film’s chorus.

“The film originally was all about Paul’s story — his recovery, his experiences,” Villena says. “But as you see in the film, his recovery is pretty miraculous — it’s mind-boggling. The idea was this: It’s great that Paul is recovering, and it’s cool for the film, but there is a much larger story. What about people who don’t recover, who can’t move anything, let alone walk with crutches? There is a broader story, about how people deal with the injury.”

Among those featured is Australian Sam Willoughby, a two-time BMX world champion who broke his neck in 2016. Also featured is Jesse Billauer, a surfer who broke his neck on a shallow sandbar in 1996, at the age of 17. And there’s Annette Ross, who was given the wrong fluid in an epidural during childbirth in 2000, burning her spinal cord, and Steph Aiello, who was in a car crash in 2010 that left her paralyzed from the waist down.

“It was all in service of Paul’s story,” Villena says. “His story benefits from those other voices to add context, to say the things he can’t speak to at that point in the film. Not only does the chorus broaden the scope, but it also gets deeper into what he was feeling and going through.”

One of the film’s toughest moments comes after Basagoitia is home from Craig Hospital, battling depression as he adapts to his new circumstances. He’s using a walker to reach his mailbox. The scene is juxtaposed against footage of him in his prime, flying through the air, making the impossible look effortless. The sequence ends with him stuffing a stack of medical bills into his back brace.

"Any One of Us" closes with Basagoitia taking his first ride since the injury. It also shows several members of the chorus making the most of life with their SCIs — forming a dance troupe, riding waves, playing basketball and walking across the stage to receive a high school diploma. It’s an uplifting end to a heavy film that leaves viewers with a deeper appreciation of their own mobility, as well as insights into the lives of those with paralysis.

I think he's found this new love for riding that he'd probably never experienced.

LIFE AFTER THE DOC

It’s February 24, the day of the 2019 Academy Awards. In a few hours, "Free Solo," the film about Alex Honnold’s attempt to become the first person to climb El Capitan without a rope, will win the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature.

I tell him I believe "Any One of Us" could be nominated for an Academy Award. A year from now, I suggest, he could be in LA, wearing a tuxedo.

“That would be very humbling,” he says. “But at the end of the day, as long as it helps somebody with this injury and we can bring some funding into finding a cure and helping people with the situation, that’s a home run for me.”

I tell him about an article I’d read about "Free Solo" that said Honnold’s friends cried as he began his ascent of El Cap because they thought they might never see him again. There was a quote from Honnold’s mother, who said that when he’s free climbing he’s truly at peace. “Who would want to take that away from him?” she asked. Though it could kill her son, she saw it was what brought him joy.

"Free Solo" demonstrates how when you push up against the edge, ultimately you find the edge. Sometimes that edge means certain death. Sometimes it means a shattered T12 vertebra and paralysis.

Basagoitia nods. Two of his closest friends, Cam Zink and Kyle Strait, have won Rampage and continue to compete. Zink, 33, is married with two children; he won the event in 2010 and finished second in 2014 and 2017. Strait, 32, was only 17 when he won Red Bull Rampage in 2004; he won it again in 2013. Both have told Basagoitia they’re delaying retirement to try to win it once more.

“It’s a lot more terrifying watching it now, and especially with guys like Kyle and Cam, really close buddies of mine,” he says. “It’s hard to see them compete, and the last thing I want any of them to do is to follow the same footsteps I did. I don’t think the reward for them is worth taking that risk. But that’s the crazy thing about being an athlete. You always want more.”

That said, Basagoitia doesn’t feel Rampage is too extreme. Changes have been implemented since his injury, including extended time to build lines, a mandatory rest day, a two-day weather window to determine when conditions are safest and the elimination of the qualification round. Organizers have also modified the judging panel to include only former Rampage competitors, increased the prize purse and added minimum travel budgets to apply toward dig teams.

“I think it’s important to have Rampage for big-mountain riders,” he says. “If it wasn’t for Rampage, a lot of these big-mountain riders would not have half the endorsements they have today. Rampage brings a lot of exposure, and it’s the only event that exists today for big-mountain riders. So obviously I’m for it.”

With spring looming, Basagoitia’s life is changing dramatically (again). He’s a few months into a new job, with upstart mountain bike footwear brand Ride Concepts. He’s managing the brand’s global athletes and helping on the creative side. He’s already assembled a team of sponsored athletes that includes Strait and the all-star Atherton siblings.

The following week, he’s headed to South by Southwest for the premiere of "Any One of Us." In April he’ll travel to the Sea Otter Classic, the largest cycling event in the United States, where he’ll be working the Ride Concepts booth. It’s a lot to look forward to, though that’s not how he would describe it.

“I get a little skeptical on things because sometimes I’m insecure about my injury,” he says. “There’s a lot of things I still can’t do. We went to this little zone in Utah last week and we had to jump over a fence and throw the bike over, and obviously I can’t do that on my own, so I had to have the whole crew help me. So when I think of Sea Otter I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to walk up all those stairs and back down those stairs.’ I’m already thinking about the struggles that are going to be in front of me.”

These are the things one contemplates living with a spinal cord injury. These are the things one contemplates living in a “new body.”

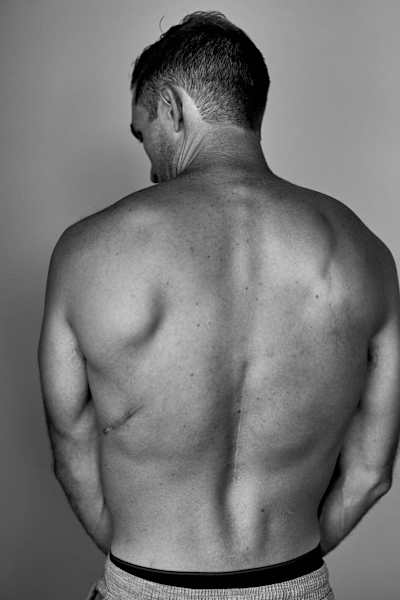

For Basagoitia, living with an SCI means a 90-minute workout every morning, focusing on core strength, building muscle and cardio. He’s come to terms with the reality that he may never regain sensation below his knees, and his glutes may never again work properly, so he’s doing everything he can to strengthen the rest of his body. Because he can’t use his glutes, he carries his weight in his lower back and relies on his hip flexors to facilitate walking. The end result is frequent soreness and occasional muscle spasms.

One of the final scenes in "Any One of Us" shows Basagoitia back on a bike. He can use his quads and his hamstrings, the two key muscle groups for pedaling, but he can’t feel the pedals; look closely as he’s riding and you’ll notice that he’s constantly checking his foot position. And while the film ends with his first ride, he’s now much farther along, riding a pedal-assist electric bike on trails, occasionally boosting a small jump.

Munk says that seeing Basagoitia on a bike again has been transformative — for both of them. “It brings a whole new happiness for him,” she says. “I think he has found this love for riding that he’d probably never experienced. I think his time on the bike before was competitive. Now the only person he competes with on a bike is 100 percent himself and I think he is finding so much joy in knowing he can push the limits. It’s healing for him. Now he’s jumping, which makes me a little nervous, but the joy he’s getting from it, what he’s posting, he’s on this crazy high, and I want to keep him on that high.”

The ability to soar through the air was already taken away from him once. It’s when he’s happiest; when he’s at peace.

THE SCI COMMUNITY

As Basagoitia adapts to his new life, he must adapt to a new role in the SCI community. He receives emails “at least once a week” from someone coping with a life-changing injury. In Reno, a friend who works in the trauma center contacts him whenever there’s a new patient with an SCI. At film festivals, he’s approached by people sharing intimate details of their challenges — everything from dealing with SCIs to depression to addiction. Suddenly, people want to confide in him.

“Paul is giving a lot of people a lot of hope, that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, that you’ve got to keep pushing,” Munk says. “When the injury happened, I think his identity was stripped from him. He’s gotten to share that you can reclaim your life and your identity. He’s been such an inspiration to so many, to not let these injuries define who you are. It’s been so cool to see that unfold. I don’t think that was part of his plan, but I think he gladly provides so much for so many people, and he doesn’t even realize it’s happening.”

Basagoitia acknowledges it’s a role he is learning to embrace, even as he struggles with it. Answering emails, or questions after a screening, is one thing. But walking into the ICU and meeting someone who just learned they may never walk again is something else.

“I let them know about my situation and what I did, and I try to give them encouragement,” he says. “I find it fulfilling, but it’s hard, too, because it brings back memories. The first two weeks with a spinal cord injury is literally the worst two weeks of your life because you’re in so much pain, you can’t move, you can’t feel. The future is unknown. I tell them ‘Just keep plugging away. Keep your head up. You never know what could happen. It’s gonna be a long road.’ ”

This advice can be applied to his own life as well. “I struggle with it, too,” he says. “I’m like, ‘Fuck, is this really me for the rest of my life?’ Reality sets in sometimes. I get in these dark moments like, man, I did not visualize my life being like this. I struggle thinking about that, and then the other side of my brain is like, ‘You’ve come so far. You’re still able to pedal your bike. You’re fully independent; you don’t rely on anybody to help you with anything. Be blessed.’ So I have that.”

With "Any One of Us" set for widespread distribution, Basagoitia and Munk’s visibility inside and outside the SCI community is about to explode. “Ideally, I hope that nothing really changes drastically,” Munk says. “I love my life and our lives together. I know that this is bigger than us, and I’m so grateful for that. But it’s also very important to stay humble, and also, there are so many people that have sustained a spinal cord injury, and they haven’t been given the opportunity to share their story."

UP IN THE AIR

Basagoitia is afraid of heights.

That might sound like dark humor coming from a man whose former career involved 60-foot gap jumps, but it’s the truth — which makes it all the more interesting that he’s now pursuing a pilot’s license. A close friend is a captain for SkyWest Airlines; after Basagoitia’s accident, he took him flying in a Cessna Skywagon. Up in the air, Basagoitia took over the controls. He banked a few turns and was hooked. His injury doesn’t prevent him from using the foot pedals; though he lacks dorsiflexion, he’s able to slow down the plane with his heels.

And in another journey, Basagoitia has reconnected with his mother. They hadn’t spoken for several years prior to his injury, and that continued well into the first year of his recovery.

“She was concerned, but I was just so focused on my recovery, I didn’t want to try to fix our relationship at the same time,” Basagoitia says. “But at the moment we chat once a week, maybe every other week. It’s a lot better now than it’s been in quite a few years.”

Perhaps she’ll attend his upcoming wedding. Soon enough, Basagoitia will be a married man. He proposed to Munk in October 2017 in Malibu, two years after his injury. In one of the final scenes in the film, he ditches his cane, walks toward her unassisted, takes a knee and pops the question. They initially discussed getting married in Tulum in Mexico but instead decided on Lake Tahoe, in part because his father doesn’t fly. They set a date of February 20, 2020 — 02/20/2020 — though that may not happen as planned.

“We’re going to be together until we die, God willing, so there’s no real rush to tying the knot,” Munk says. “We’re still coming down from the filming, and the film festivals. We just haven’t been able to make it a priority to plan a wedding.”

And while he might be using a cane, when the day comes, Basagoitia will be walking, not wheeling, down the aisle.

And what about the long-term future? What about having kids? For now it’s a maybe — and still a possibility — as one of the lighter, more uplifting scenes in "Any One of Us" makes clear.

“We always talk about whether we’re going to have kids or not,” Basagoitia says. “Right now, we don’t see us having kids anytime soon. But it doesn’t mean that we won’t. When I was hurt, the last thing I wanted was to have a child and not be able to show them how to ride a bike, or walk around the park. That would kill me, not holding your own kid, throwing him up in the air. It was scary at one point, knowing that that might never happen. I could show them how to ride a bike, though — I can still do that. Maybe not throw him up in the air, but I could definitely show him how to ride a bike."

THE LEGACY QUESTION

We’re back to the bike ride in the Mount Rose Wilderness on a hot day in June. We’ve reached the top of the climb. We’ve stopped to catch our breath and enjoy the view. The hardest part is now behind us.

It’s like Basagoitia’s life in this moment. The hardest part is behind him. But it will never be easy. It’s all a matter of perspective at this point, reconciling what he used to have with what he has now — and with what might have been. On one hand, he’s an elite athlete who used to fly through the air with grace. On the other hand, he is able to walk with just one cane. And he can ride a bike again.

“My dad always joked that I was able to pedal a bike before I was able to walk,” he says. “It was true, and it’s true again.”

Before his injury, he scratched and clawed and beat the odds. After his injury, he did the same.

Part of maintaining that perspective is reconciling his new identity with who he was prior to his injury. “This injury is going to be tied to me for the rest of my life,” he says. “Even when I post a video or a photo of me riding bikes, people are like, ‘Oh, I’m so stoked to see you back on a bike again.’ I’ve been on the bike for the last two years, three years. Yeah man, I’m back on the bike. I’ve been on the bike for years.”

That seems like a natural and well-intentioned comment, I counter. What would be a better thing for them to say?

“‘Nice riding style,’” he says. “Or ‘Looking good on the bike.’ I don’t know the right answer, but every time I post a photo of me riding, it’s just ‘Stoked to see you back on the bike after your injury.’ It’s always related to the injury, everything I do. I could see like the first year or two years, but now we’re on three years.

“And that was one thing about this film. I have accomplished a lot of cool things in mountain biking. I’ve really done some bitchin’ things in this sport. But my legacy is going to be known for this fucking accident. People forget about the Crankworx title. People forget I was the first person to do a 720 on a mountain bike. People forget all of that. I’m going to be known for making one big mistake. My legacy is going to be known as the kid who got paralyzed at Rampage.”

But it’s all part of the same legacy, I tell him. It’s all tied together. Before he was injured, Basagoitia inspired people. After his injury, he still inspires people. Before his injury, he scratched and clawed to beat the odds. After his injury, he did the same. He didn’t accept his fate. He fought back. He overcame the odds.

That, I assert, is Basagoitia’s story.

“I think that was the story of my whole life,” he says. “Growing up, living in a hotel room, showing up to the biggest event, Crankworx, with a borrowed bike, no sponsors. I’ve been an underdog my whole life. With this injury, with the likelihood of me to ever recover as much as I did, I was definitely an underdog. So if I was known for that — ‘That dude got dealt some shitty cards but he always made the best out of the situation, he always fought back’ — then I’ll be happy.”

Ultimately, whether he likes it or not, that will be his legacy. The page turned when he suffered a spinal cord injury. But it was not the last chapter.

“I won’t have to look back,” he says. “I’m going to keep looking forward. One of my buddies gave me the best advice. He said, ‘You can’t always look back in life, Paul; all that does is gives you a sore neck.’ And that’s so fucking true.”

And with that, in a cloud of dust, Basagoitia is gone, gracefully flying down the trail at an impressive rate of speed. All the rest — the film festivals, the new job, the physical therapy, planning a wedding — will wait. In the moment, he is back in his natural flow state, fully at peace. For the moment, he is not looking back. He is looking forward.

"Any One of Us" premieres October 29 on HBO and is available to stream on demand October 30.